Let’s see why Brussels’ Tech Enforcement in 2026 Has Washington Talking Retaliation.

Table of Contents:

- EU Tech Laws and the US-EU Trade Tensions

- Enforcement moves that sparked retaliation

- Trump threatens tariffs under Section 301

- Clashing views on competition and censorship

- Why US tech firms oppose the rules

- Europe’s case for regulating market power

- Why 2026 Is a Turning Point for Digital Sovereignty and Trade

- Broader effects on trade and global politics

- What comes next: talks or conflict

EU Tech Laws and the US-EU Trade Tensions

This growing conflict between EU regulation and US protectionism is one of the biggest threats to transatlantic economic relations since Trump’s first trade wars. Billions of dollars in fines, tariffs, and access to key markets are now at stake.

The dispute centres on two EU laws that have reshaped how tech companies operate in Europe: The Digital Markets Act, which limits anti-competitive behaviour by dominant platforms, and the Digital Services Act, which sets rules on online content and safety.

Both laws are already in force and have led to large fines for US tech giants. As the EU prepares to launch more investigations and penalties in 2026, the Trump administration has made clear it sees these rules as economic aggression and is ready to respond.

Enforcement moves that sparked retaliation

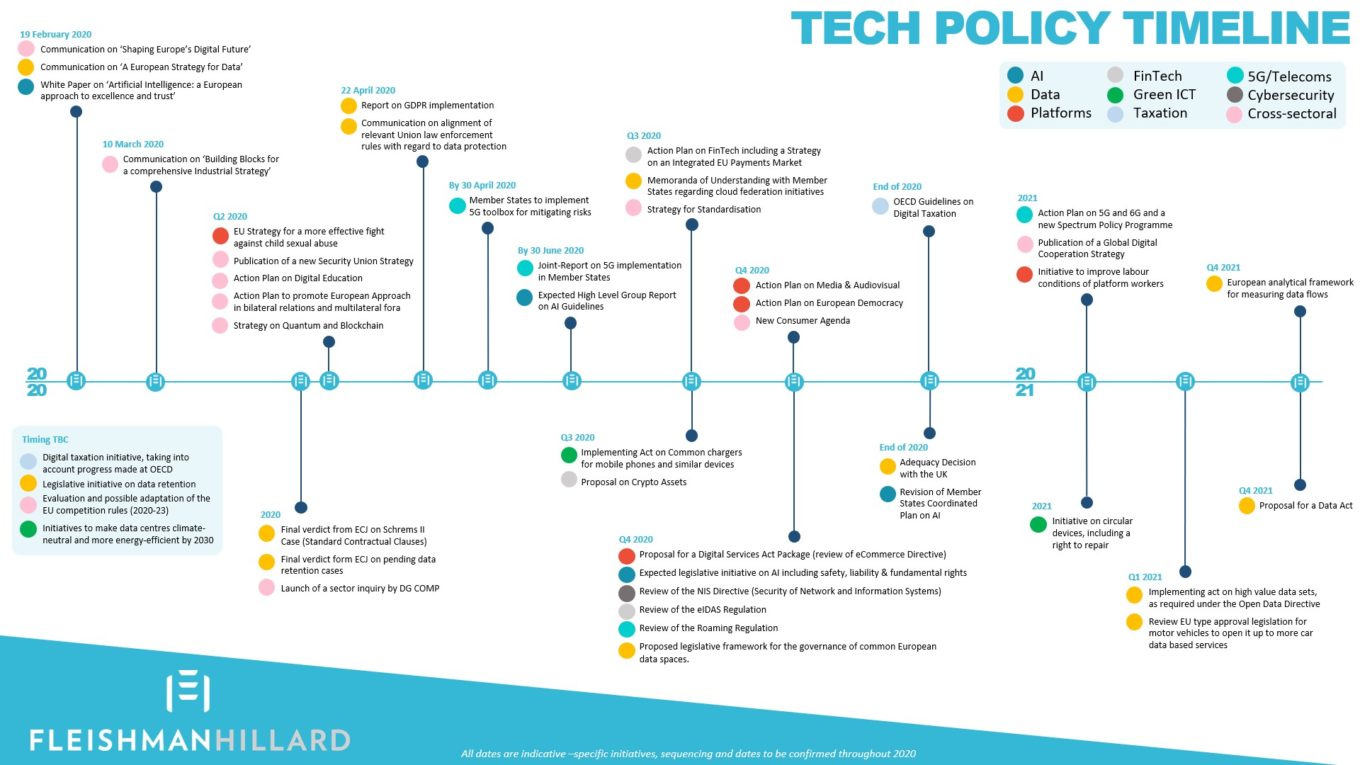

The European Union has positioned itself as a global leader in tech regulation through laws such as the AI Act, the Digital Services Act, and the Digital Markets Act. Over the past year, Brussels has increased enforcement to limit the power of major tech companies including Amazon, Apple, Google, Meta, and Microsoft.

Recent fines show how serious this push has become:

- In April 2025, Apple and Meta were fined €500 million and €200 million for breaching the DMA.

- In September 2025, Google received a €2.95 billion fine for breaking EU competition rules in online advertising.

- In December 2025, Elon Musk’s platform X was fined €120 million under the DSA for failing to meet transparency and Content moderation requirements.

EU Competition Commissioner Teresa Ribera has made clear these fines are only the beginning. Despite criticism from the US and from global tech firms, she has said enforcement will continue as part of Brussels’ broader approach to Digital sovereignty.

The DMA, which has applied fully since May 2023, sets strict rules for so-called gatekeeper platforms that can control Market access for other businesses. Six companies have been designated so far: Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, ByteDance, Meta, and Microsoft. Five of them are based in the United States.

From the EU’s perspective, the DMA is meant to make digital markets fairer by:

- limiting self-preferencing,

- encouraging interoperability,

- restricting how platforms use data.

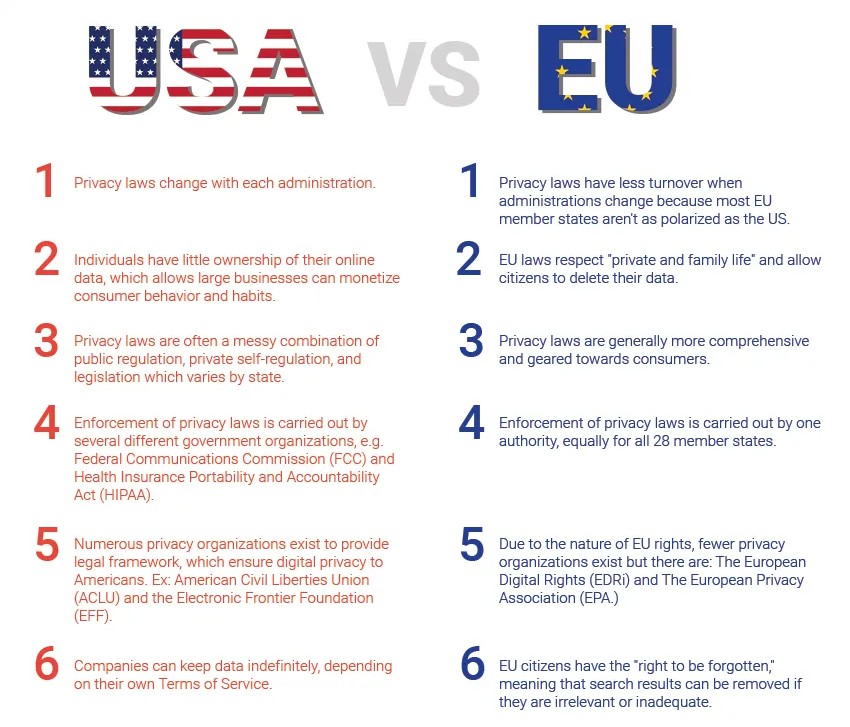

From Washington’s point of view, however, this approach looks less like consumer protection and more like disguised protectionism.

Trump threatens tariffs under Section 301

The Trump administration has taken a hard line against EU tech regulation. The US Trade Representative accused Brussels of repeatedly targeting American companies through lawsuits, fines, taxes and regulatory orders.

Washington has warned it is ready to retaliate using all available tools. This could include fees or restrictions on European companies operating in the US. Firms named as possible targets include Spotify, DHL, Accenture, Siemens, SAP, Amadeus IT Group, Capgemini, Publicis Groupe and Mistral AI. US officials have pointed to what they describe as the illegal scope Spotify issue as evidence of unfair treatment.

The main tool for retaliation is Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974. This law allows the US to investigate foreign trade practices it sees as unfair and, if violations are found, to impose tariffs or quotas. Such action would likely trigger an EU tariff response from Brussels.

Trump has used Section 301 before, especially against China, and has shown he is willing to use it again. In September 2025, he threatened higher tariffs on the EU after the Google fine, putting the existing trade agreement at risk.

That agreement, reached in July 2025, lowered tariffs on most EU exports to the US to 15 percent and included a commitment by the EU to buy 750 billion dollars of US energy products by 2028. A new investigation could undo this deal and lead to a new trade conflict.

Clashing views on competition and censorship

Behind the legal debate on competition and antitrust is a deeper disagreement about how far governments should go in regulating digital platforms.

European policymakers see the Digital Markets Act and the Digital Services Act as necessary because they believe a small number of large platforms hold too much power.

In their view, these gatekeepers limit competition and innovation. The rules are meant to open digital markets so new companies can compete fairly, instead of being blocked by firms that control key infrastructure.

The DSA focuses on another issue. EU lawmakers argue that large platforms strongly influence public debate and online safety but are not accountable enough for the content they host. The law requires platforms to remove illegal content, be more transparent about how their algorithms work, and allow users to challenge Content moderation decisions.

Former European commissioners supported this view in a commentary published on January 2, 2026. They said the US government misunderstands the purpose of the DMA and DSA, which they argue are designed to limit the power of dominant platforms and improve accountability, not to control speech.

American critics see the situation very differently. They argue the DMA does not focus on consumer harm or wrongdoing but instead targets companies for being large, successful, and mainly American. From their perspective, innovation is being treated as a problem, while foreign competitors gain access to data and technology they did not create.

The disagreement is even stronger on Content moderation. Trump administration officials have accused the DSA of enabling censorship. In response to EU enforcement actions, the US barred five European officials from entering the country, including former internal market commissioner Thierry Breton. Washington argues that EU regulators are using their powers to restrict speech that would be protected under the First Amendment.

Overall, this is more than a policy dispute. It reflects two different views of markets and freedom. Europe sees regulation as necessary to protect competition and democracy. The Trump administration sees it as an attack on American businesses and free speech.

Why US tech firms oppose the rules

From the perspective of US tech companies, EU rules are costly to follow, create legal uncertainty and force changes to products that work well in other markets.

The Digital Markets Act requires companies labelled as gatekeepers to:

- open their platforms to third-party apps and app stores,

- support cross-platform messaging,

- stop favouring their own services,

- share data with business users.

For companies like Apple and Google, this means redesigning key products and opening closed systems to competitors.

Meta has also had to adjust its advertising model. After the European Commission ruled it was not complying with user choice rules, the company said that from January 2026 EU users will be able to choose between fully personalised ads or ads based on less data.

Industry groups say these rules slow innovation and create technical and security problems that harm user experience. They also argue the system is unfair, as non-designated competitors face fewer rules while US companies carry most of the burden.

As a result, many in Silicon Valley now see Europe as an adversary rather than a partner, using regulation to pressure successful American companies while protecting weaker European rivals.

Europe’s case for regulating market power

European officials deny that EU tech rules are aimed at the US. They say the DMA and DSA apply to all companies that meet the criteria, no matter their nationality. The fact that most gatekeepers are American reflects how the market works, not bias.

The European Commission also rejects claims that these laws are non-tariff barriers. It argues that the rules respect freedom of information and treat all companies equally, regardless of where they are based.

According to the Commission, platforms already make most decisions themselves. Its digital spokesperson said that more than 99 percent of Content moderation actions in the EU are taken by platforms under their own rules. The EU says it is not telling companies what to remove but asking them to apply their own policies properly.

European officials also argue that digital markets are dominated by a few large platforms because of network effects and high switching costs, not fair competition. Regulation is needed because the market has not fixed these problems on its own.

For Europe, the DMA is also about helping European companies compete. If US platforms control key digital infrastructure, European businesses become dependent on them, which limits local innovation and shifts value abroad.

Why 2026 Is a Turning Point for Digital Sovereignty and Trade

Both sides are now firmly set in their positions, making 2026 a key year for relations between the EU and the US on technology.

In Europe, enforcement will increase. The EU’s AI Act becomes fully enforceable in August 2026, marking an important step in Brussels i regulation. Companies using high-risk AI in areas such as hiring, law enforcement and healthcare will have to carry out impact assessments and ensure human oversight.

The Digital Markets Act will also be reviewed. By May 3, 2026, the European Commission must assess whether the DMA is meeting its goals, how it affects businesses, especially smaller firms, and whether changes are needed.

Cloud computing is also becoming a new focus. In November 2025, regulators opened investigations into Amazon and Microsoft’s cloud services. This shows that Brussels readies enforcement not only for platforms like social media and search, but also for core internet infrastructure.

In the United States, the Trump administration appears ready to move forward with retaliation. Washington is preparing a Section 301 investigation that could lead to tariffs, arguing that EU rules are discriminatory. The US has warned that similar rules in other countries could also face retaliation, raising the risk of a broader EU tariff response.

Political pressure is increasing as well. The House Judiciary Committee has held hearings on what it calls unfair foreign regulations based on the DMA, framing the issue as protecting American innovation.

The debate is no longer about whether the US will act, but when and how strong the response will be.

For EU B2B businesses, the risk of retaliation and disrupted Market access in 2026 is also a reminder that strengthening European partnerships and diversifying sourcing within the EU is becoming a strategic priority.

Broader effects on trade and global politics

The dispute between the EU and the US over tech rules is part of wider tensions that also affect trade, defence, data flows and geopolitics.

For European businesses, the risks go beyond regulatory costs. A trade war between the EU and the US would disrupt supply chains, raise prices and create uncertainty that slows investment. European tech startups could be hit especially hard, as many rely on US funding and Market access.

The dispute also makes it harder for Western countries to agree on how to govern technology in competition with China. The EU focuses on early regulation, while the US is moving toward tougher antitrust action.

Even though both sides say they want fair markets, consumer protection and democratic control of technology, they have not found common ground. This reflects deeper political and economic concerns on both sides.

What comes next: talks or conflict

There are several possible ways forward, but none are easy.

One option is negotiation. During trade talks in summer 2025, the US proposed creating a DMA advisory body so companies could give input on enforcement. The EU rejected the idea, saying it would weaken its authority.

Another option is limited exemptions. The EU could apply lighter rules to some US companies in exchange for trade concessions. However, this would go against the EU principle that rules must apply equally to all companies, regardless of nationality.

A third option is escalation. If the Trump administration moves ahead with Section 301 tariffs, the EU would likely respond with its own trade measures. This could lead to a wider economic conflict, with both sides raising pressure until a political solution is forced.

The most likely outcome is a long period of tension with occasional compromises. Neither side wants a full trade war, but neither is willing to give up on its core positions. As a result, EU B2B companies are likely to place greater emphasis on local and European partnerships to reduce exposure to transatlantic disruptions.

Conclusion

If the EU and the US cannot find common ground, the transatlantic digital economy could split. This would increase costs for businesses, reduce operational flexibility and weaken cooperation between democratic partners.

Industrial B2B sectors most exposed include cloud and data infrastructure, industrial software, logistics and freight, advanced manufacturing, automotive supply chains, aerospace, and energy systems.

With stronger enforcement in Europe and possible retaliation from the US, the stakes in 2026 are very high.

For more ideas on EU digital regulation, europages Inside Business offers helpful tools and inspiration.